Shoeing Welfare

Shoeing with regard to Equine Welfare

Clive Meers Rainger RSS Bll CNBF CLS

Shoeing with regard to Equine Welfare

We have all heard the saying "no foot no horse" but do we realise what shoeing can do for the horse or, for that matter, how it can cause lameness and long-term damage? To understand how it might we must first briefly describe how a hoof works and then in turn, relate it to different types of shoeing.

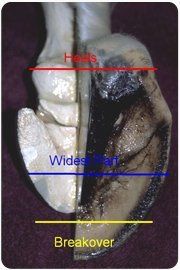

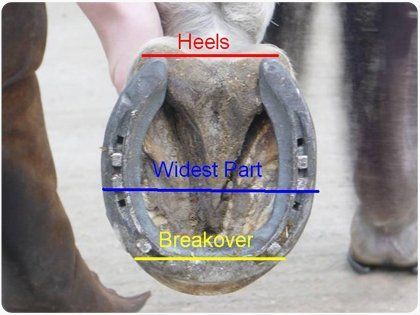

Looking at the bottom of the foot, it can be divided into two halves, using the widest part of the foot as a dividing line. The horn is flexible and therefore the widest part of the hoof has to equate to the widest part of the largest solid object within the hoof, which is the pedal bone (or coffin bone).

The shape and size of the hoof capsule reflects the dimensions of the pedal bone, the largest solid object within the foot

This is also the centre of articulation of the last joint of the limb, known as the coffin joint, or to use it's technical term the distal inter-phalangeal joint (distal meaning furthest from the body and phalanges being the bones of the pastern).

The bones of the lower limb

The widest part of the foot is approximately 1" back from the point of the frog and is where the bars that run from the heels along each side of the frog terminate into the sole.

From the widest part of the foot forward the sole is thicker, with an area known as the sole callus, which has a much denser horn to protect the tip of the pedal bone. The hoof wall at the front of the hoof is wider and the laminae which form it are more densely packed together. This is because the front half of the hoof has to give stability to the column of bones and give protection to the pedal bone and because the horn is attached to a solid object, the pedal bone, it is the least flexible half of the hoof.

In the back part of the foot we find the walls are much thinner, but should thin gradually and extend back to the widest part of the frog before they return back to the widest part of the hoof in the form of the bars, which run either side of the frog. Four-fifths of the frog is in the back half of the hoof and in this area the sole should be concave and is designed to flex upwards when the back half of the hoof makes contact with the floor during the landing phase of the stride.

Simply put, the front half of the hoof gives stability and the back half gives function.

There are three phases to a stride:

1. Phase one if the stride is the landing of the foot, which should be heel first so that the frog can push upwards into the digital cushion, helping to dissipate the energy created by the foot impacting the ground. As the frog pushes into the digital cushion, the lateral cartilages (which lay either side of the hoof and extend from the front of the foot, where they attach to the front and sides of the pedal bone, right back to the heels) are expanded and lifted. The most effective way of dissipating kinetic energy is to force liquid through a tube. In this case the liquid is blood and the tubes are the vascular system which is most plentiful in the digital cushion. The blood in the digital cushion acts like hydraulic fluid as it is squeezed out of the hoof, helping dissipate the kinetic energy.

Horse displaying heel landing both in front and behind

2. The second phase of the stride is the weight-bearing phase, when the foot is flat on the ground and the column of bones carries the weight of the horse as it passes over the foot. At this moment the frog is pushed fully into the digital cushion and the pedal bone is held in a more upright position, ready for the third part of the stride. It is during this phase that the toe engages with the ground and the heels lift as the body weight passes through the vertical. It is at this moment that the power of the horse begins to push the horse forward, as shown by the wear that may be found on the toe of a worn shoe.

3. The moment the toe engages and the heels start to lift is called "the point of breakover". It should happen just as the body weight passes over the vertical column of bones. The sooner the heels lift, the longer the back part of the stride will be, and the more power will be generated through the toe to drive the horse forward, as the horse is designed to push itself forward, not pull itself along. The back part of the stride should be equal to the distance the limb travels forward when tracking up, when a horse is moving in a straight line.

These distances and the internal function of the hoof can however be dramatically affected if the measurements of the bottom of the hoof are changed. By this I mean the distance from the widest part of the foot forward to the toe becomes greater than the distance back to the widest part of the frog, as in a long toed horse.

As the toe becomes longer, the first phase of the stride goes from heel landing to landing flat and eventually to toe landing, thus removing the horses ability to absorb concussion and levering the pedal bone backward in the hoof capsule, instead of lifting it. This then forces the horse to become heavy on the forehand as it has to adapt itself to pulling rather than pushing itself along, producing an unnatural, rolling movement of the shoulders as it uses them to help lift the hoof over the long toe.

Extreme example of a long toe and low weak heels

Long toes behind can cause the pelvis to tilt, which in turn causes pain in the region of the saddle, giving the horse a high head carriage and again forcing the horse onto the forehand.

Now we can begin to see how the feet can affect the whole horse, which leads us onto shoeing. Firstly, what is known as "traditional" shoeing which has been developed over the centuries for horses that were worked in straight lines at a walk or trot, either in harness or as a mode of transport taking its owner from A to B. These shoes were made to be wider and longer than the hoof from the centre back to give maximum support to the functional back half of the hoof and going in straight lines at slow paces reduced the likelihood of overreaching and loosing shoes.

A traditionally shod hind foot - note how much more length is in front of the widest part of the foot than behind it

These shoes were also only on for two or three weeks before they were worn out and needed to be replaced. Indeed, in the 1950 British Horse Society Manual of Horsemanship it states that if your shoes aren't worn out in three weeks, book an appointment with your farrier so that he may remove the surplus foot growth to keep your horses limbs in balance.

Many years ago I used to shoe hunters at Melton Mowbray. These horses did twenty miles of roadwork a day, getting them fit for purpose and every extra day we could go before shoeing was considered a bonus, three weeks being the maximum we could achieve. Working horses in this was gave rise to the misconception that shoes should only replaced when they are worn out. If horses are in hard work this is the case, but as it is through the toe that power generated in the muscles is transmitted into forward movement, it therefore follows that it is the toe that is meant to wear and by putting shoes around the toe we prevent this from happening. If hoof balance is not maintained and the shoes are left on too long the toes elongate and a slow slide into lameness starts.

Today's horses do very little work on abrasive surfaces or in straight lines. They generally work on a soft surface in a school and in circles which means the backs of the shoes are fitted short and tight to reduce the probability of lost shoes. When support is removed from the back of the hoof, nature compensates by increasing horn production in the front of the foot to try to maintain the pedal bone in it's correct position, causing the toe to elongate faster and reducing still further the function and ability to absorb concussion. This removal of support from the back of the hoof both reduces the ability for the foot to absorb concussion and prevents the pedal bone from lifting into the position needed for the third phase of the stride.

Unfortunately, with a traditional shoe on the foot, the toe is unable to wear and therefore increases the speed at which the toe becomes long and ultimately the heels will collapse.

These days however there are a number of early break-over shoes which remove leverage from the toe enabling the farrier to give greater support to the back half of the hoof as they are placed around the pedal bone rather than around the toe. This allows any surplus toe to wear provided the heels are lowered to the widest part of the frog. The shoes are fitted bold from the widest part of the hoof back and, most importantly, the wall at the front of the hoof is left in situ, only removing any flares. Removing excessive wall from the toe removes stability causing the hoof to over expand.

The most well known of these early break-over shoes are "Natural Balance" shoes, who also make "Centre Fit" shoes. These are made with the middle of the shoe marked; if the marks are placed at the widest part of the foot break-over will occur just in front of the front edge of the pedal bone. They are also graduated from the centre to the outer rim of the shoe reducing leverage in all directions, helping circular movements on soft surfaces and preventing the joints from reaching the extremes of articulation when turning and reducing repetitive strain injuries which are becoming all the more common in modern horses and are so very hard to diagnose.

A Natural Balance early break-over shoe - the distance from the widest part of the foot back is the same as or greater than the distance forward to the toe

As our horses are asked to do a greater variety of jobs and are no longer as fit as they were in the past, we must look to improve bio-mechanics to enable them to perform without the risk of injury, finding the appropriate style to suite the horses conformation, intended use and surface on which they are to be worked.

Many people refer to modern techniques as remedial, but as all types of shoes have been designed to help the horses to remain sound while working and most shoes we refer to as traditional were designed for horses in heavy work on hard ground, it therefore follows that we have changed both how we use horses and the surfaces we use them on and have also lengthened the periods between shoeing, we need to change how we approach the horses requirements from a farriers' perspective.

Clive Meers Rainger RSS Bll CNBF CLS

April 2010

“ I have no doubt that it is wholly though Clive’s skill and patience that Fig is still with us today and is comfortably enjoying his happy retirement… Thank you.”

Julia

“Just a word of thanks, to you Clive, for your consistently outstanding care for the horses.”

Mark

Get in touch with Clive

If you would like to know more about Equine Foot Protection or you have specific question about Natural Balance Farriery or to discuss your particular Farriery needs or just to book an appointment please fill out the for below and we will get back to you

Thank you for contacting us.

We will get back to you as soon as possible

We will get back to you as soon as possible

Oops, there was an error sending your message.

Please try again later

Please try again later

About EFP

With over 45 years of experience Clive has dedicated his career to Farriery and the care of Equine Athletes and Friends alike

Contact info

The Forge, Gabriels Farm, Marsh Green Road, Nr Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 5PP

+44 7884 236892

equinefootprotection@gmail.com